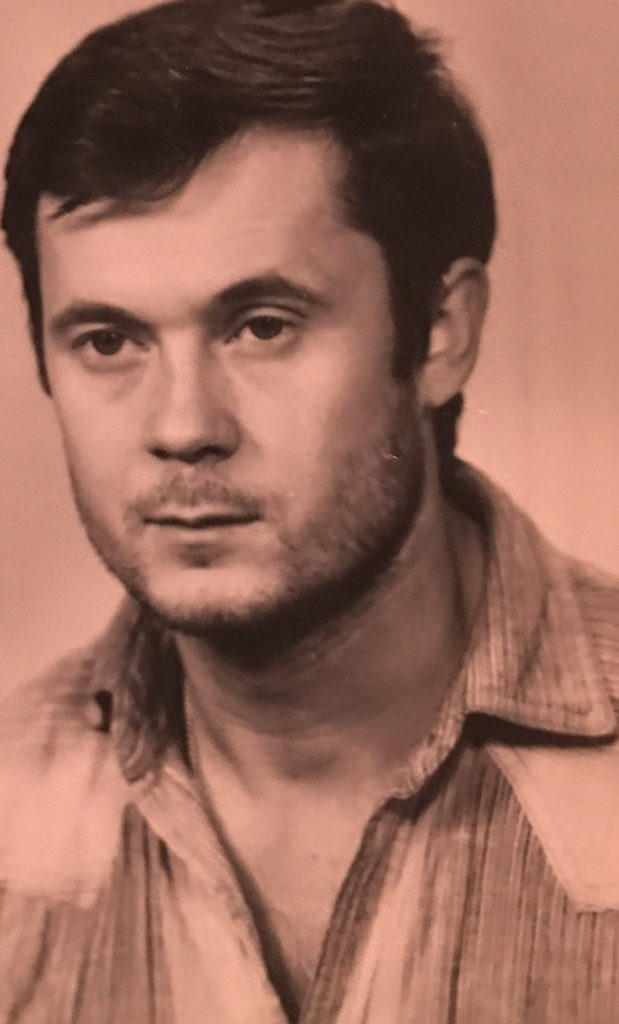

What do stoics and poets have in common? It just happens that my husband Jerzy is both. One way to describe a stoic that I found in a dictionary is “a person who is not very emotional. The adjective stoic describes any person or action or thing that seems emotionless and almost blank.”

Actually Jerzy is the contradiction of that statement – he is very emotional. I believe that what got him in trouble when he was younger and became an alcoholic was his emotions. What got him out of it was emotions as well, strong feelings of friendship, comradeship, loyalty and love for the sport of weightlifting. His intense drive to succeed in the Moscow Olympics almost got him fatally injured, yet the road to recovery brought out the best in him. Studying for years, researching and searching for solutions to overcome limitations, injuries and restrictions made him into an outstanding coach and a perceptive mentor.

The object of alcoholism was different, the aim was different, but the passion and drive was the same. I know very little of Jerzy the Alcoholic, at the beginning of our relationship he was already a self-motivated, top student, and a great athlete.

“Creatures that look backwards”—I remember someone once said this about poets. Poets are feeling beings, they connect to emotions and still try their best to live in the present. Their writing reflects how engaged, observant, sensitive or curious they are in the moment. What they focus on that steers them. What bothers them about the world, people, politics, belief systems, or something as simple as daily living. What or who they admire, are in awe of and look up to. Philosophers (including stoics) on the other hand, try to intellectually understand feelings and emotions. The poet and the philosopher in Jerzy are his entwined Gemini.

The description of a stoic also says, “to endure pain or hardship without a display of feelings or complaint.” It seems to me that Jerzy’s striving in life always has been to understand human existence, searching for how to ease the unnecessary suffering of his human fellows. Just a little bit and as much as he can. Wherever we go or no matter who we interact with, Jerzy is always encouraging others for education. That’s where it starts. He sees people as they can be, not what they are now. His dogma is captured well by Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe in this quote: “If we treat people as they ought to be, we help them become what they are capable of becoming.”

When we immigrated to Sweden other refugees used to call Jerzy the village priest and would seek emotional support from him to cope with the horrendous stress of being an immigrant, never knowing what the future held. He helped many, finding the right words in the right time for the right person.

Nothing goes shallow with Jerzy, a conversation cannot be a simple exchange, there must always be something to learn or discover. Whatever subject he wanted to explore—aromatherapy, music therapy, nutrition, human anatomy, even chiropractic medicine—he learnt in depth. When we decided to sell our house he simply studied and took the brokerage exam as an exercise to understand the real estate business. Jerzy’s mission is to understand the mind, feelings and emotions in service of self-improvement. He even got a hypnotherapy certification to dig deeper into his own psyche.

“The past is not interesting” is one of his favorite sayings, a way to let go of the burden of events in the past. Yet I’ve lived with this modern-day stoic for close to forty years, and I’ve seen and experienced many ups and downs during those years. The best and the worst, all the grievances and joys were paving the road to where we are we now.

I witnessed firsthand how Jerzy dealt with the most difficult moments in his life. Some of them became turning points, changing the course of his life and affecting mine. It started when we got married. He proposed at the beginning of his first year at the Fire Engineering Academy in Warsaw. Marriage required the permission of the dean of the school. The answer was “no” of course, and the school went as far as offering money for an abortion, in case I was pregnant. We got married anyway, but kept it a secret.

What I saw in Jerzy over the years was not a stoic “being calm and almost without any emotions” but someone using emotions to do the right thing, even if it meant going against the grain, putting his life at stake. When the Solidarity Movement at its height his dissertation was almost completed, and we looked forward starting a new chapter in life that would involve less struggle and more ease. With a well-paid job and an apartment of our own, we could plan to become a family.

But Jerzy couldn’t just be a bystander while the government ordered fire department student officers to turn hoses on demonstrators, marking them with colored water so they could be easily identified and prosecuted for their participation. The students were in that school to learn how to serve people, not to be used as weapons against them. That was against his fundamental ethics.

The protest lasted ten days. I was there watching with fear and awe how a group of young people fought for what was right despite the consequences, and how the public stood by them, offering emotional and moral support. Even preschoolers from the building next door were throwing their lunches over the fences; elderly people left boxes with donuts, something simple to say ‘We are with you, you are not alone, keep going.’ And they did—a group of them stood their ground. Despite pressure from the government and special forces, despite the parents whose fear told them to withdraw, and friends who didn’t want to lose them, begging them to stop.

Whenever we are going through difficult times, I often ask Jerzy if he regrets any decisions he has made in the past, and he always says, “No, it made me into the man I am today.” He is a man of principle and ethics and carries a strong sense of what’s right or wrong, and sticks with his commitment.

I see how both emotional intelligence and stoicism are needed to progress in life. The power of a stoic is to be constructive. Crises and opportunities give people a choice to respond to life with grace, and challenge them to become better human beings. Jerzy is the kind of guy that when life throws lemons his way, he will make lemonade (with a splash of vodka!), a marinade for fillet mignon, or even a…lemon meringue pie. And love and commitment are his persistent ingredients.

DEEPER CONTEMPLATION

Do you agree with Jerzy’s saying, “Hard choices, easy life; easy choices, hard life”? Can you think of one example from your life that follows this principle?

Leave your response below in the comments.

I’m making a decision right now to leave a well-paid job, that has provoked great anxiety in me, for my own wellbeing. Hard choice. Hard hard choice, looking forward to the ease that comes after and even during.

I do really encourage you to do. I have also been in a similar sitaution and I preferred quiting before damade arrives.